Hydropower: Benefits, Energy Balance, and Ecological Impact

In a world increasingly focused on sustainable living and reducing our carbon footprint, renewable energy sources are paramount. Among them, hydropower stands as a long-established and powerful contender. As New Zealand pioneers a sustainable future, understanding technologies like hydropower is crucial for informed decisions about our energy landscape.

This article delves into the multifaceted world of hydropower, exploring its significant benefits, analysing its energy balance, and examining its crucial ecological impacts. Join us as we unpack how this age-old technology continues to shape our path towards a cleaner, more resilient energy future.

1. The Enduring Benefits of Hydropower

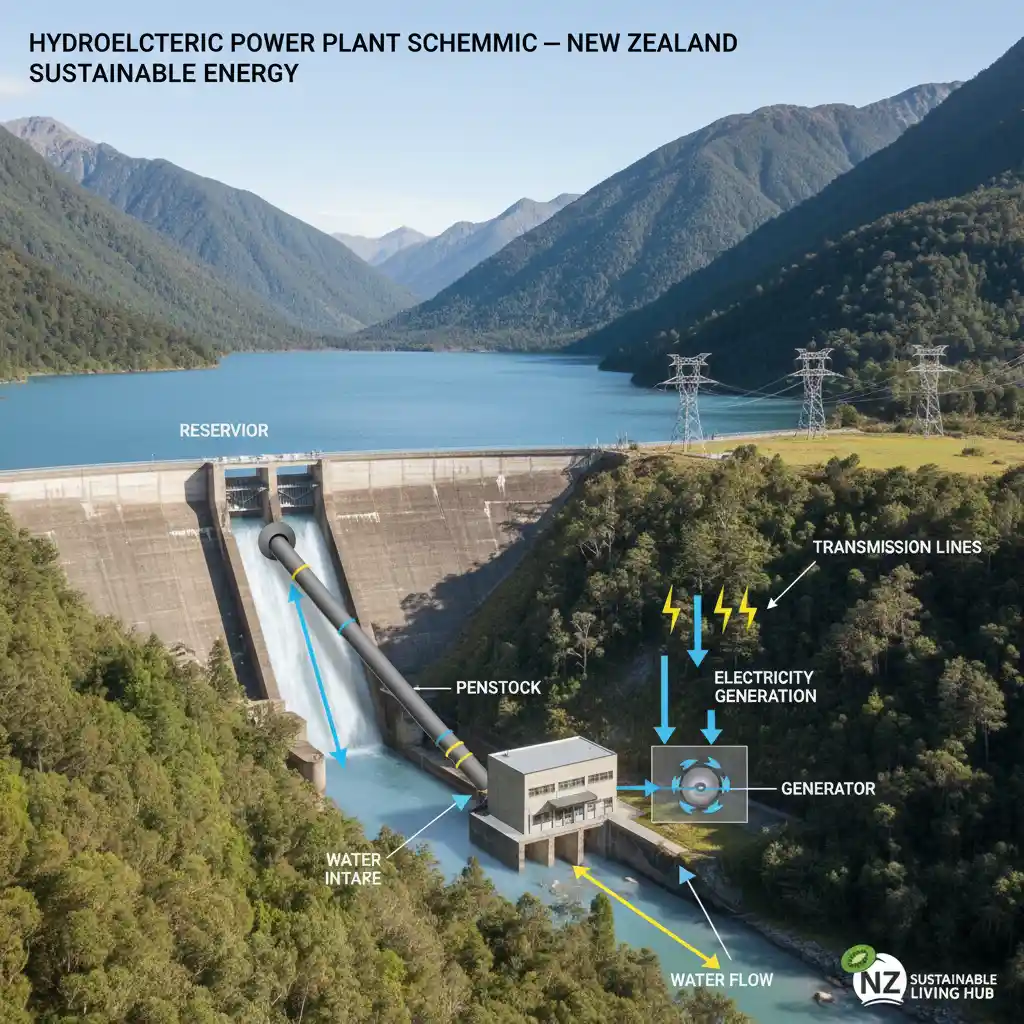

Hydropower, harnessing the kinetic energy of flowing water, offers a compelling array of advantages that make it a cornerstone of sustainable energy portfolios worldwide. Its inherent characteristics contribute significantly to energy security and environmental goals.

Renewable and Sustainable

As long as the water cycle continues, hydropower remains an inexhaustible energy source. It doesn’t consume water but rather uses its flow to generate electricity, making it a truly renewable resource. This contrasts sharply with fossil fuels, which are finite and contribute to resource depletion.

Low Carbon Emissions (Operational)

During operation, hydroelectric plants produce virtually no greenhouse gas emissions. This makes them a critical tool in combating climate change and reducing air pollution, especially when compared to coal or natural gas power plants.

Reliability and Grid Stability

Unlike intermittent renewables like solar and wind, hydropower offers exceptional reliability. Water flow can often be regulated, providing a steady and predictable power supply. This stability is vital for balancing the grid and ensuring constant access to electricity.

Flexibility and Energy Storage

Hydro plants can quickly start up and shut down, adjusting output to meet fluctuating demand. Many also offer pumped-hydro storage, where excess electricity (e.g., from solar/wind during off-peak hours) is used to pump water uphill, storing energy for later release. This acts as a giant natural battery.

Economic Benefits

Beyond energy, large hydropower projects often bring additional benefits such as flood control, irrigation, and water supply management. They can also create local jobs and stimulate regional economic development.

2. Understanding Hydropower’s Energy Balance

When evaluating any energy source, it’s crucial to look beyond the immediate output and consider the entire lifecycle, including the energy invested in its creation and maintenance. This is where concepts like Energy Return on Investment (EROI) and Life Cycle Assessment become vital.

Energy Return on Investment (EROI)

EROI measures the ratio of energy delivered by an energy source to the energy required to deliver it. Hydropower generally boasts a very high EROI, indicating it produces significantly more energy than it consumes throughout its lifespan, from construction to decommissioning. This is a strong indicator of its efficiency as an energy producer.

Stat Callout:

Some studies suggest that large-scale hydropower projects can have an EROI ranging from 50:1 to over 100:1, making it one of the most energetically efficient forms of electricity generation. For every unit of energy invested, 50 to 100 units are returned. (Source: White & Kulcinski, 2007)

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)

An LCA provides a comprehensive evaluation of the environmental impacts associated with all stages of a product’s (or system’s) life, from raw material extraction through processing, manufacture, distribution, use, repair and maintenance, and disposal or recycling. For hydropower, LCA considers the energy and materials used for dam construction, turbine manufacturing, transmission lines, and the operational footprint. When these are factored in, hydropower still typically has a lower overall carbon footprint than most fossil fuel alternatives.

Efficiency and Modernisation

Modern hydropower facilities are designed for optimal efficiency, converting a high percentage of water’s potential energy into electricity. Ongoing technological advancements and modernisation of older plants further enhance their energy output and reduce their environmental impact. This continuous improvement ensures hydropower remains competitive and valuable in the energy mix.

3. Navigating the Ecological Impact and Challenges

While hydropower offers significant benefits, it’s not without its environmental and social challenges. A balanced understanding requires acknowledging and addressing these impacts, many of which are site-specific and depend on the scale and design of the project.

“Every energy source has an impact. The goal for sustainable development is to choose those with the lowest net impact, considering both environmental and socio-economic factors over their entire lifecycle.”

Habitat Alteration and Biodiversity Loss

The construction of dams creates large reservoirs, often submerging vast areas of land. This can lead to the loss of terrestrial habitats, forests, and agricultural land, displacing wildlife and potentially endangered species. Downstream, altered river flows can also impact aquatic ecosystems and fish migration patterns.

Sedimentation and Water Quality

Dams trap sediment that would naturally flow downstream, affecting river morphology and nutrient distribution. Reservoirs can also experience changes in water temperature, oxygen levels, and nutrient cycling, which can harm aquatic life and impact water quality for downstream communities.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions (Reservoir Methane)

While operational hydropower is low-carbon, reservoirs, particularly in tropical regions or where significant biomass is submerged, can emit methane (a potent greenhouse gas) from the decomposition of organic matter. The exact contribution of these emissions to climate change is a subject of ongoing research, but it’s an important factor in the full environmental assessment.

Social and Cultural Impacts

Large dam projects can displace local communities, disrupt livelihoods, and impact cultural heritage sites. Ensuring equitable compensation, resettlement, and community engagement is critical for ethical hydropower development.

Mitigation Strategies

To minimise these impacts, modern hydropower planning incorporates environmental impact assessments, fish ladders, minimum flow requirements, sediment flushing protocols, and careful site selection. Run-of-river schemes, which have smaller reservoirs or none at all, also offer a lower-impact alternative in suitable locations.

4. Hydropower in New Zealand’s Sustainable Future

New Zealand has a long and proud history of hydropower, with it forming a significant portion of the nation’s electricity generation. The country’s abundant rainfall and rugged topography have made it an ideal candidate for hydro development. As NZ continues its journey towards a 100% renewable electricity target, hydropower will remain a crucial baseload and flexible energy source, balancing other renewables like wind and solar.

Future developments are likely to focus on optimising existing infrastructure, exploring small-scale or run-of-river projects where appropriate, and investing in pumped-hydro storage to enhance grid resilience, all while prioritising environmental stewardship and community engagement.

5. Conclusion

Hydropower represents a powerful and mature renewable energy technology with numerous benefits, including reliability, low operational emissions, and significant energy efficiency. While challenges related to ecological and social impacts exist, ongoing research and advanced mitigation strategies are continuously improving its sustainability profile.

For New Zealand and other nations striving for a sustainable future, hydropower will undoubtedly continue to play a vital role in providing clean, consistent power, balancing grid demands, and supporting the broader transition away from fossil fuels. A balanced and informed approach is key to harnessing its full potential responsibly.

6. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Is hydropower truly renewable?

A: Yes, hydropower is considered a renewable energy source because it relies on the natural water cycle, which is continuously replenished by the sun’s energy. It doesn’t deplete the resource it uses (water) but rather harnesses its flow.

Q: What is the EROI of hydropower?

A: Hydropower generally has a very high Energy Return on Investment (EROI), often ranging from 50:1 to over 100:1. This means it produces a significantly greater amount of energy than is required to build and operate the power plant over its lifetime, making it highly energy-efficient.

Q: How does hydropower impact fish populations?

A: Hydropower dams can impede fish migration, alter habitats, and change water flow and temperature regimes, which can negatively impact fish populations. However, modern projects often incorporate mitigation strategies such as fish ladders, bypass channels, and tailored flow management to minimise these effects.

Q: Can hydropower reservoirs contribute to climate change?

A: In some cases, yes. Reservoirs, especially in tropical regions or where significant organic matter is submerged, can release methane (a potent greenhouse gas) as this matter decomposes. However, the overall lifecycle emissions of most hydropower projects are still significantly lower than fossil fuel power generation.

Q: What are the main challenges for future hydropower development?

A: Key challenges include finding suitable sites with minimal environmental and social impact, managing the initial capital cost, addressing climate change impacts on water availability, and gaining social acceptance through comprehensive stakeholder engagement.

7. References & Sources

- International Hydropower Association (IHA). (Various years). Hydropower Status Report.

- World Energy Council. (Various years). World Energy Trilemma Index.

- White, J. L., & Kulcinski, G. L. (2007). Energy payback ratio: a review of the literature. University of Wisconsin–Madison.

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Hydropower and the environment: A guide to impact assessment and mitigation.

- Ministry for the Environment, New Zealand. (Various publications). Environmental Reporting Series.

- NZ Electricity Authority. (Various publications). New Zealand Electricity Market Information.